DEEP BRAIN STIMULATION FOR TREATMENT-RESISTANT SCHIZOPHRENIA

In this section

Deep brain stimulation could be an option for some severely treatment-resistant patients, although there are several things that need to be worked out, not least where to place the electrodes, was highlighted at the 33rd European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) Congress, held online 12–15 September 2020.

The use of deep brain stimulation for some symptoms of schizophrenia seems to be a promising approach, acknowledged Professor of Psychiatry Stefano Pallanti, MD, PhD, who chaired an educational symposium on the topic. However, the lack of a comprehensive theory of how it actually works and the fact that schizophrenia is a disorder with a wide spectrum of symptoms may hinder its use, noted Prof. Pallanti, who is the Director of the Institute for Neurosciences in Florence, Italy.

During the symposium, issues such as assessing the capacity to consent to the procedure, the risks involved in the surgical placement of the electrodes, and the results of one of the first completed trials of deep brain stimulation in schizophrenic patients were presented.1

Why deep brain stimulation?

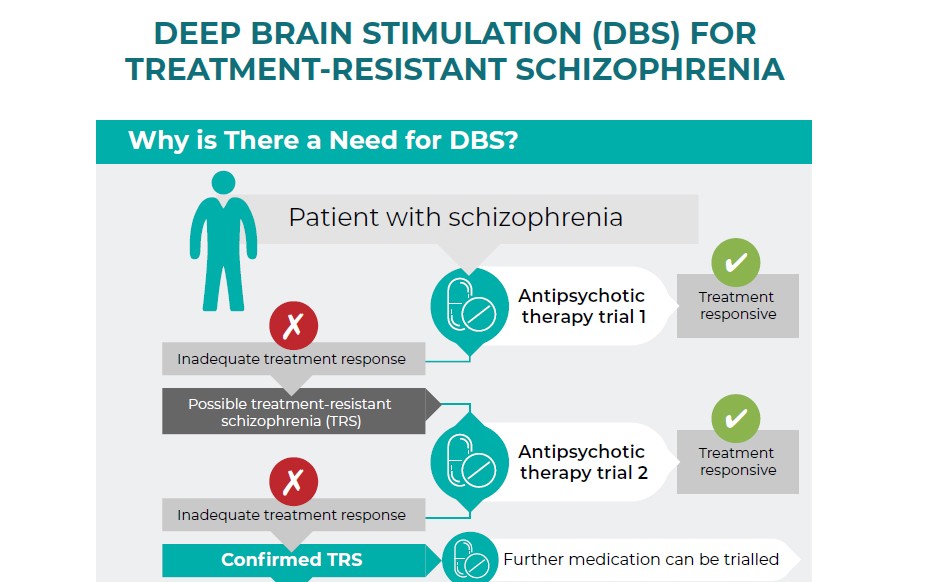

Despite advances in drug therapy, 20–30% of patients with schizophrenia do not respond to antipsychotic medication even if they are compliant with the treatment.1 In recent years, deep brain stimulation has gained interest as a treatment in this patient group because of its successes seen in neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy. Such results have fuelled optimism that deep brain stimulation might also be an effective treatment option for patients with psychiatric disorders such as major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Currently, there are many unmet medical needs for individuals with schizophrenia, thus new therapeutic options such as deep brain stimulation are now being embraced, said Judith Gault, PhD, who is an Associate Research Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of Colorado in the United States. Although there is a chance that it may not work in this patient group, it is imperative to move forward, she said. Nonetheless, moving forward needs to be done with caution, Prof. Gault added.

Having treated people with schizophrenia for the past 20 years, Prof. Gault is one of the researchers who are now looking into the potential for deep brain stimulation to help those who have limited treatment options remaining. In particular, Prof. Gault and her team are interested in resolving the ethical concerns around the use of this technique and identifying electrophysiological biomarkers that could be used in order to conduct a clinical trial in psychotic patients. They are currently recruiting patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who are interested in learning more about deep brain stimulation and how it might help them.

How is deep brain stimulation performed?

Deep brain stimulation involves the attachment of a stereotactic frame to the patient’s head and then the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and stereotactic planning software to visualise the area of the brain that needs to be targeted. Electrodes are then implanted in the targeted area of the brain and linked to a pulse generating device that is implanted under the collarbone or in other suitable area of the body. Psychiatrists then program the pulse generating device accordingly.

Given its invasiveness, it is very important to consider the ethics of doing this, Prof. Gault said. For guidance, she recommended the Belmont Report2, which covers the ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects in research. There are three main tenets of this report: the respect of persons – which means practitioners need to make sure that the individual has capacity to consent; beneficence – which involves the examination of the overall risk versus benefit; and justice – the insurance of equitable distribution of risk and burden and benefits.

At present there are no legally defined objective criteria on how to assess someone’s capacity to consent, Prof. Gault noted. However, there are some tools that can be used by researchers such as the California Scale of Appreciation3 and the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research.4

Does it actually work in schizophrenia?

The severity and refractoriness of schizophrenia justify the use of deep brain stimulation, suggested Damiaan Denys, PhD, Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He also noted that there is a very acceptable risk-benefit ratio.

Prof. Denys added, however, that there are two major challenges in understanding if the technique could work in schizophrenia. The first being that schizophrenia is a very complex and heterogenous disorder that does not appear to have a single target in the brain that links all the different symptoms that patients exhibit. This raises the problem of where to place the electrodes. The second challenge is that patients need to be motivated, and not only agree to participate in trials, but also be able to consent to the treatment in the first place. They also need to understand that it is a lifelong treatment that will require commitment to continual check-ups and monitoring. Prof. Denys noted that one trial had to stop because of the difficulty in recruiting patients.

Many of the areas of the brain that might be targeted with deep brain stimulation have something to do with a change or disbalance in dopamine,5 Prof. Denys observed. The nucleus accumbens for instance, which is part of the ventral striatum, is a very popular target for deep brain stimulation in other psychiatric disorders. Besides the nucleus accumbens, the medial prefrontal cortex and substantia nigra could be other possible targets for such treatment.

Nonetheless, there is limited evidence to date that deep brain stimulation works in patients with schizophrenia. One recently completed study1 was presented by Iluminada Corripio, MD, PhD, who works at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona, Spain. The study included eight patients and had an initial open-label 6-month design, followed by a 24-week double-blind, cross-over period. For inclusion, participants had to be resistant to at least two different antipsychotics, have not responded to clozapine either alone or in combination, as well as not responding to electroconvulsive treatment. After inclusion, electrodes were placed either in study subjects’ nucleus accumbens or their subgenual anterior cingulate cortexes.1

Dr. Corriprio reported that one of the eight patients did not receive deep brain stimulation due to complications of the surgery (haemorrhage and infection). Of the other seven who received treatment, a 25% improvement measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scale was seen in a substantial proportion of patients during the open phase, and several of the patients showed worsening in symptoms when deep brain stimulation was discontinued.

These preliminary findings suggest that deep brain stimulation may be a potential option for treatment-resistant patients, Dr. Corriprio said. It is not for all schizophrenia phenotypes though, she cautioned, noting that future work should be looking to include patient-centred recovery programmes, family interventions and cognitive behaviour therapy alongside the deep brain stimulation.

References

- Corripio I, Roldan A, Sarro S, et al. Deep brain stimulation in treatment resistant schizophrenia: a pilot randomized cross-over clinical trial. EBioMedicine. 2020; 51: 102568.

- Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The Belmont Report. 1979.

- Saks ER, Dunn LB, Marshall BJ, et al. The California Scale of Appreciation: a new instrument to measure the appreciation component of capacity to consent to research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002; 10 (2): 166–74.

- MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). In: Kreutzer J.S., DeLuca J., Caplan B. (eds) Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. Springer, New York, NY.

- Gault JM, Davis R, Cascella NG, et al. Approaches to neuromodulation for schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018: 89: 777–87.